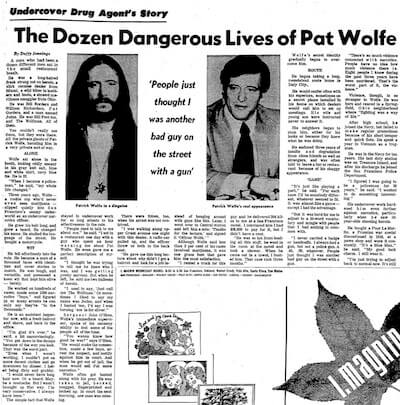

The Dozen Dangerous Lives of Pat Wolfe

My article, from November 15, 1972

The city editor said, “Bob Popp at the police beat says there’s a cop named Patrick Wolfe who’s been an undercover narc for the past three years and now wants tell his story. Go talk to him.” I met Wolfe in a restaurant. He was a nice looking man in his 30s, wearing a suit and tie. My story ran in the paper November 15, 1972.

He was a long-haired freak strung out on heroin, a slick cocaine dealer from Miami, a wild biker in leathers and boots, a shrewd marijuana smuggler from Ohio.

He was Bill Borders and William Richardson. Pat Gorders, and a man named Judas. He was Bill Fent too, and The Wolfman. All of them.

You couldn’t really see them, but they were there. All the private ghosts of Patrick Wolfe, haunting him in a very private sort of way.

Wolfe sat alone in the booth, looking oddly uneasy in his gray knit suit, blue and white shirt, navy blue tie. He is 33.

“When I became a policeman,” he said, “my whole life changed.”

Three years ago, Wolfe — a rookie cop who’d never even seen marijuana – slipped quietly into San Francisco’s seamy underworld as an undercover narcotics officer.

He grew his hair long, and grew a beard. He changed his name. He studied the language of the street. He bought a motorcycle.

He fell effortlessly into the role. He became a man of a thousand faces with identities and cover stories to match. He was tough, and versatile, and possessed a keen wit that kept him alive — barely.

He worked on hundreds of cases, made some 1500 narcotics “buys,” and figured in so many arrests he can only say they’re “in the thousands.”

He is an assistant inspector now, with a fresh haircut and shave, and back in the office.

“I’m glad it’s over,” he said, a bit unconvincingly. “You get down in the dumps because of the way you look. That was the worst part.

“Even when I wasn’t working, I couldn’t put on some decent clothes and go downtown for dinner. I hated being dirty and grubby.

“I would never have long hair now. Or a beard. Maybe a mustache. But I wasn’t brought up that way. I’m very conservative. I always have been.”

The simple fact that Wolfe stayed in undercover work for so long attests to his effectiveness in the role.

“People used to talk to me about me,” he said. “I sat in a restaurant one day with a guy who spent an hour warning me about Pat Wolfe. He even gave me a perfect description of myself.

“I thought he was trying to tell me he knew who I was, and I was getting pretty nervous. But when he left, he sold me two balloons of heroin.

“I used to say, ‘Just call me The Wolfman.’ Or sometimes I liked to say my name was Judas, and when I busted ’em, I’d say I was turning ’em in for silver.”

Sergeant John O’Shea, Wolfe’s immediate supervisor, spoke of his uncanny ability to fool some of the people all of the time.

“You wanna know how good he was?” says O’Shea. “He would make the connection, make a few buys, arrest the suspect, and testify against him in court. And when he got out of jail, the man would sell Pat more narcotics.”

Wolfe often got busted along with his prey. He was taken to jail, booked, mugged, fingerprinted and locked up. In court the next morning, one man was missing.

There were times, too, when his arrest was not contrived.

“I was walking along upper Grant avenue one night with this dealer. A radio car pulled up, and the officer threw us both in the back seat.

“He gave me this long lecture about why didn’t I get a haircut and look for a job instead of hanging around with guys like this. Later, I went over to Central station and left him a note: ‘Thanks for the lecture,’ and signed it Officer Wolfe.”

Although Wolfe said fewer than 3 per cent of his cases involved marijuana, it was one grass bust that gave him the most satisfaction.

“I rented a truck for this guy and he delivered 204 kilos to me at a San Francisco motel. I convinced him I had $38,000 to pay for it, but I didn’t have a cent.

“He was so hot from loading all this stuff, he went in the room at the motel and took a shower. When he came out in a towel, I busted him. That case took three months.”

Wolfe’s secret identity gradually began to overcome him.

He began taking a long, roundabout route home in Daly City. He would confer often with his superiors, sometimes on a secret phone installed in his home on which dealers would call him to set up meetings. His wife and young son were instructed never to answer it.

His neighbors began to shun him, either for his looks or because they knew what he was doing.

He endured three years of insults and degradation from close friends as well as strangers, and was often told to leave a bar or restaurant because of his shaggy appearance.

“It’s just like playing a part,” he said. “For each case I’d be somebody different, whatever seemed to fit. It was almost like a game — except I had the advantage.

“But it was hard for me to adjust to a 50-word vocabulary and mingle with people that I had nothing in common with.

“I never carried a badge or handcuffs. I always had a gun, but not a police gun. A .45, .38, whatever. People just thought I was another bad guy on the street with a gun.

“There’s so much violence connected with narcotics. People have no idea how much violence there is. Eight people I knew during the past three years have been murdered. That’s the worst part of it, the violence.”

Violence, though, is no stranger to Wolfe. He was born and reared in a Springfield, Ohio neighborhood where “fighting was a way of life.”

After high school, he joined the Navy, but failed to make regular promotions because of his short temper and quick fists. He spent a year in Vietnam as a frogman.

He was in the Navy for ten years. His last duty station was on Treasure Island, and after his discharge he joined the San Francisco Police Department.

“I figured I was going to be a policeman for 20 years,” he said. “I wanted to do something interesting.”

His undercover work hardened him even further against narcotics, particularly when he saw 10-year-olds shooting heroin.

He bought a Pour Le Merite, a Prussian war medal discontinued in 1918, at a pawn shop and wore it constantly. “It’s a Blue Max,” he said. “My good luck charm. I still wear it.

“I’m just trying to adjust back to normal now. It’s still hard for me to carry on a normal conversation.

“It was a dangerous job, sure. But I suppose I’d do it again if they wanted me to.”

Wolfe glanced casually over his shoulder, a reflex he may have to live with for a very long time. He knows there are those who would like to kill Bill Borders, or Judas, or The Wolfman.

“It was very lonely,” he said, as he and the dozen other men who live inside him walked quietly outside into the pouring rain.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR