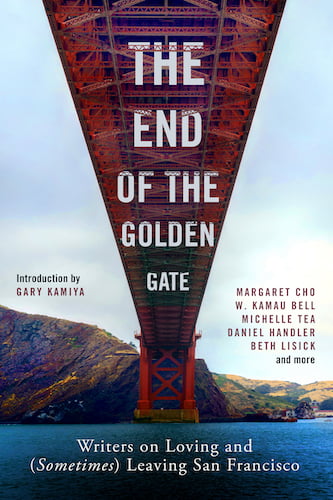

THE END OF THE GOLDEN GATE

Writers on Loving and (Sometimes) Leaving San Francisco

San Francisco is a city that has changed vastly over time, shapeshifting to become something different for every generation.

Over the years, millions of people have loved to call San Francisco home, yet gentrification and the radical cost of living have compelled many to consider leaving.

I’m very proud to be included in this collection of beautiful, heart-wrenching essays that take on the Bay Area-dweller’s eternal conflict: Should I stay or should go?

Order a copy of The End of the Golden Gate and help those who choose to stay! A portion of the profits will go to support families experiencing homelessness in the San Francisco Bay Area.

AN EXCERPT

“PAPER BOY”

FROM THE END OF THE GOLDEN GATE

By Duffy Jennings

I must have been about ten when I got my first paper route, delivering the afternoon San Francisco News-Call Bulletin in the Cow Hollow neighborhood where I lived. This was in the late 1950s, when a kid my age with a paper route was no more unusual than a ten-year-old riding the Muni alone out to Playland-at-the-Beach or sitting by himself in the Saturday double feature.

After school, I’d wait on the street corner near my house for the circulation manager’s blue panel truck with the newspaper’s logo on the side. He’d pull up to the curb, open the sliding side door from the inside, toss a twine-wrapped bundle of fifty or so papers on the sidewalk, and take off. I divided the stack between the front and back pouches of my shoulder bag and slung it over my head. The white canvas sack smelled of fresh newsprint and ink, and the dead weight of it—worse on Thursdays with the big advertising sections for weekend shoppers—sometimes felt like I was lugging the printing press itself up the hills until it gradually emptied.

Folding papers as I walked, I tossed them onto driveways and stoops, up flights of stairs to porches, over metal gates to front walkways. We didn’t have plastic bags then, so if it was raining, I had to make sure the paper ended up in a dry spot. Sometimes I used what we called the “tomahawk” fold, bending the paper into a scalene triangle of sorts with a rock-hard point that, when flung overhead, hatchet-style, enabled greater distance without coming apart in mid-air. The dense, rigid point of it was so stiff that an errant throw could break a window. And did more than once. At an apartment building, I’d walk down a side alley to the garage entrance and climb the inside stairwell to the top. Then I’d work my way down floor-by-floor, dropping papers with a soft thud at the door of each subscriber in the building.

By the time I got home for dinner my hands were smudged black and my shoulders ached. Carriers were also responsible for collecting the subscription payments. At the end of every month, I went to each of my customers’ homes around dinner time and rang the bell, calling out: “Collecting for the News-Call!” I liked the idea that I was providing this important service and information to my neighbors, though I was too young to understand why. And it felt good to earn my own spending money for a new model airplane or candy at the movies.

That paper route was my first job, but not my last delivering the news. Ten years later I became a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. What I didn’t already know about the city before then I learned on that job. It exposes you to every neighborhood, every culture, and every kind of event. It opens doors to the centers of power and prestige, and it takes you to the dark underside of city life. You meet the famous, the infamous, the criminal, the rich, the poor, and the average citizen. Every day you learn something new, meet someone different, hear a story for the first time—you see and report on the best and worst of the city. It’s an immersion education into the good, the bad, and the ugly of all things San Francisco that few natives ever get.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR