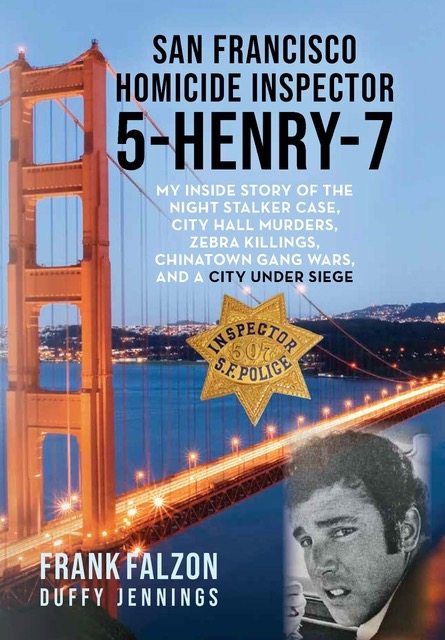

5-Henry-7:

A San Francisco Homicide Detective’s Memoir of Serial Killers & Political Assassinations

The Inside Story of the Night Stalker Case, City Hall Murders, Zebra Killings, Chinatown Gang Wars, and a City Under Siege.

San Francisco Homicide Inspector 5-Henry-7 is retired detective Frank Falzon’s intensely personal inside story of an extraordinary career investigating one high-profile murder case after another during the ultra-violent 1970s and 1980s—a period one crime expert calls the “golden age of serial murder.” Now for the first time, Falzon shares details about thirteen of the most riveting murder cases that rocked San Francisco in his day and the techniques he employed to solve them.

Among them are the notorious Night Stalker, the City Hall murders of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk by Falzon’s childhood friend and former fellow cop Dan White, the Zebra serial killings, Chinatown gang murders, and the rise of the deadly counterculture underground that targeted police. He also writes about a savage home invasion by a frenzied killer-rapist, the murder of a Holocaust survivor that went unsolved for six years until fingerprints were finally computerized, and his off-duty, face-to-face street corner gun battle with an armed robber.

San Francisco Homicide Inspector 5-Henry-7⏤Falzon’s individual radio call sign⏤sheds new light on how detectives worked to solve cases in a time without cell phones, ubiquitous surveillance cameras, computerized fingerprints, or DNA technology.

PRAISE FOR 5-HENRY-7

〝Frank Falzon is an icon, an SFPD legend. He got all the big cases. He is to San Francisco what Frank Serpico and Eddie Egan are to New York.

〝The reason Frank Falzon is a legend is that he earned it. From the Zodiac and Doodler to the Night Stalker, he worked the most infamous homicide cases in the wildest days of modern San Francisco, and he always dug in hard while somehow still retaining a big heart. He is a true cop’s cop.

〝The reason Frank Falzon is a legend is that he earned it. From the Zodiac and Doodler to the Night Stalker, he worked the most infamous homicide cases in the wildest days of modern San Francisco, and he always dug in hard while somehow still retaining a big heart. He is a true cop’s cop.

〝The reason Frank Falzon is a legend is that he earned it. From the Zodiac and Doodler to the Night Stalker, he worked the most infamous homicide cases in the wildest days of modern San Francisco, and he always dug in hard while somehow still retaining a big heart. He is a true cop’s cop.

〝Frank Falzon is the quintessential San Francisco cop … smart, tough, and loyal, with a heart of gold. He confronted and solved crimes during the most challenging times in San Francisco history. His real-life story easily eclipses the myth of Dirty Harry.

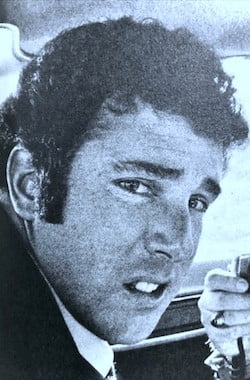

Inspector 5-HENRY-7

Frank Falzon

TV APPEARANCES

Watch Inspector Falzon and Duffy Jennings in their fascinating Commonwealth Club interview to discover the real detective work that went on behind the scenes back then.

AN EXCERPT

“You Never Know”

The thing about a murder scene is, you never know what you’re walking into.

Over all my years as a San Francisco police homicide inspector during the ultra-violent seventies and eighties—the “golden age of serial murder,” as renowned crime historian Harold Schechter put it—there were times I thought I’d seen everything. But the crime scene I walked into on Sunday, August 18, 1985, topped them all.

I was wrapping up a quiet week on call with my partner, Inspector Carl Klotz. We hadn’t caught a new case all week and were spending Sunday morning catching up on paperwork in the homicide detail office at San Francisco’s Hall of Justice, the city’s police headquarters. We looked forward to our weekend solitude when we were on call. The nice thing about working on weekends is that we had the office to ourselves. We had time to discuss cases in relative quiet and to organize files for the week ahead without the constant din of weekdays. Come Monday, the office would be abuzz with other inspectors talking among themselves, trying to be heard over the clamor, making phone calls. District attorneys, inspectors from other details, lab guys, street cops, reporters, and others dropped in to talk about the latest cases. It could be hard to concentrate.

Carl and I lived near one another across the Bay in Marin County, so we had driven in together that morning, as we often did. We crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, breezing into the city without the usual weekday rush hour traffic. The fog that typically cloaks the bridge and the western edge of the city on summer mornings was just burning off, leaving behind a few clouds and patches of blue sky. It was still cool, in the low sixties, but promising to warm up by the afternoon. We stopped for donuts on Van Ness Avenue, got to the office, put on a fresh pot of coffee in the kitchen, and got to work.

Somewhere around ten-thirty, I said to Carl, “Let’s take a break and get out of here for a while. I need to swing by Goodman’s to pick up a new faucet for that in-law unit I’m remodeling.”

We drove out to Goodman Lumber, a San Francisco institution for do-it-yourselfers needing wood, hardware, tools, and building supplies. It was on Bayshore Avenue in the southeast part of town, near Candlestick Park. We were browsing around the store when my pager vibrated on my hip. It was the SFPD Operations Center trying to reach us. Seldom, when my beeper went off, was it good news. Almost always it brought word of a new murder.

We walked quickly out to the radio car and got in. I usually drove because I get queasy riding in the passenger seat. I’ve always had an inner ear disorder that causes sporadic attacks of vertigo. I started the engine and waited for the radio to power up, then grabbed the microphone from its holder on the dash and pressed the button.

“5-Henry-7 to headquarters,” I said, using my individual radio call sign. The number five designated the Inspectors Bureau, Henry was phonetic for the H in Homicide, and I was inspector number seven in the detail. Carl was number four.

“Yes, 5-Henry-7?”

“You paged us, headquarters. What’s up?”

“We have patrol officers from Taraval Station on the scene of a one-eighty-seven at a private residence at 1620 Eucalyptus Drive,” replied the dispatcher, using the penal code section for murder. “The coroner has been notified.”

“5-Henry-7 and 5-Henry-4 responding to 1620 Eucalyptus,” I confirmed. “Please roll the crime lab and the photo unit. Let ’em know we’re on our way.” I replaced the mike and shifted the lever of the old four-door, unmarked blue Ford Fairlane into gear.

Headquarters replied, “Ten-four, 5-Henry-7.”

“So much for our quiet week,” I said to Carl as we pulled out of Goodman’s parking lot.

It was a fifteen-minute trip across town. Eucalyptus Drive is in the southwest corner of the city, just a block from Lake Merced and close to the San Francisco Zoo and the Harding Park Golf Club.

I knew the Lakeshore neighborhood well. It’s a well-manicured, upper-middle-class residential section not far from Ocean Beach and the Outer Sunset District, where I had lived with my family for many years. My kids had gone to school and played in the area. My wife and I went out to dinner in the Sunset on weekends. The Sunset and Lakeshore were respectable neighborhoods, not used to violence. A murder in a private home in a quiet area like this was rare. I was thinking it could be a domestic dispute or some other kind of family argument gone terribly wrong.

Two black-and-whites sat in front of the house as we pulled up. The house was a tidy gray-and-white, two-story, stucco-and-wood building, with flowers and shrubs in planters flanking both sides of the driveway. A stairwell on the right side of the house led up to the front door. The living area was on a single floor over the garage. I noticed Captain Mike Lennon, the commanding officer of Taraval Station, talking to a reporter in the driveway. On the outside, everything appeared serene. As I said, you never know what you’re walking into. As homicides go, this one shattered the norm.

The thing about a murder scene is, you never know what you’re walking into.

Over all my years as a San Francisco police homicide inspector during the ultra-violent seventies and eighties—the “golden age of serial murder,” as renowned crime historian Harold Schechter put it—there were times I thought I’d seen everything. But the crime scene I walked into on Sunday, August 18, 1985, topped them all.

I was wrapping up a quiet week on call with my partner, Inspector Carl Klotz. We hadn’t caught a new case all week and were spending Sunday morning catching up on paperwork in the homicide detail office at San Francisco’s Hall of Justice, the city’s police headquarters. We looked forward to our weekend solitude when we were on call. The nice thing about working on weekends is that we had the office to ourselves. We had time to discuss cases in relative quiet and to organize files for the week ahead without the constant din of weekdays. Come Monday, the office would be abuzz with other inspectors talking among themselves, trying to be heard over the clamor, making phone calls. District attorneys, inspectors from other details, lab guys, street cops, reporters, and others dropped in to talk about the latest cases. It could be hard to concentrate.

Carl and I lived near one another across the Bay in Marin County, so we had driven in together that morning, as we often did. We crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, breezing into the city without the usual weekday rush hour traffic. The fog that typically cloaks the bridge and the western edge of the city on summer mornings was just burning off, leaving behind a few clouds and patches of blue sky. It was still cool, in the low sixties, but promising to warm up by the afternoon. We stopped for donuts on Van Ness Avenue, got to the office, put on a fresh pot of coffee in the kitchen, and got to work.

Somewhere around ten-thirty, I said to Carl, “Let’s take a break and get out of here for a while. I need to swing by Goodman’s to pick up a new faucet for that in-law unit I’m remodeling.”

We drove out to Goodman Lumber, a San Francisco institution for do-it-yourselfers needing wood, hardware, tools, and building supplies. It was on Bayshore Avenue in the southeast part of town, near Candlestick Park. We were browsing around the store when my pager vibrated on my hip. It was the SFPD Operations Center trying to reach us. Seldom, when my beeper went off, was it good news. Almost always it brought word of a new murder.

We walked quickly out to the radio car and got in. I usually drove because I get queasy riding in the passenger seat. I’ve always had an inner ear disorder that causes sporadic attacks of vertigo. I started the engine and waited for the radio to power up, then grabbed the microphone from its holder on the dash and pressed the button.

“5-Henry-7 to headquarters,” I said, using my individual radio call sign. The number five designated the Inspectors Bureau, Henry was phonetic for the H in Homicide, and I was inspector number seven in the detail. Carl was number four.

“Yes, 5-Henry-7?”

“You paged us, headquarters. What’s up?”

“We have patrol officers from Taraval Station on the scene of a one-eighty-seven at a private residence at 1620 Eucalyptus Drive,” replied the dispatcher, using the penal code section for murder. “The coroner has been notified.”

“5-Henry-7 and 5-Henry-4 responding to 1620 Eucalyptus,” I confirmed. “Please roll the crime lab and the photo unit. Let ’em know we’re on our way.” I replaced the mike and shifted the lever of the old four-door, unmarked blue Ford Fairlane into gear.

Headquarters replied, “Ten-four, 5-Henry-7.”

“So much for our quiet week,” I said to Carl as we pulled out of Goodman’s parking lot.

It was a fifteen-minute trip across town. Eucalyptus Drive is in the southwest corner of the city, just a block from Lake Merced and close to the San Francisco Zoo and the Harding Park Golf Club.

I knew the Lakeshore neighborhood well. It’s a well-manicured, upper-middle-class residential section not far from Ocean Beach and the Outer Sunset District, where I had lived with my family for many years. My kids had gone to school and played in the area. My wife and I went out to dinner in the Sunset on weekends. The Sunset and Lakeshore were respectable neighborhoods, not used to violence. A murder in a private home in a quiet area like this was rare. I was thinking it could be a domestic dispute or some other kind of family argument gone terribly wrong.

Two black-and-whites sat in front of the house as we pulled up. The house was a tidy gray-and-white, two-story, stucco-and-wood building, with flowers and shrubs in planters flanking both sides of the driveway. A stairwell on the right side of the house led up to the front door. The living area was on a single floor over the garage. I noticed Captain Mike Lennon, the commanding officer of Taraval Station, talking to a reporter in the driveway. On the outside, everything appeared serene. As I said, you never know what you’re walking into. As homicides go, this one shattered the norm.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR