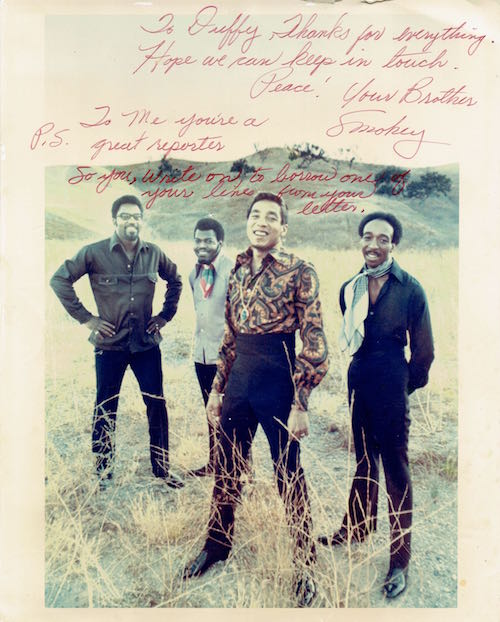

smokey robinson

Smokey sent this to me after my article was published.

Like many others around the country in 1970, I was a huge Motown fan, and the Miracles were performing in town, so I cajoled Daily Datebook editor John Stanley into letting me interview Robinson. After making arrangements with his publicist, I saw the show that night and then went to his hotel room the next morning. Smokey answered the door in a white terry bathrobe, invited me in and asked if I minded waiting while he excused himself for a quick shower. “Sure,” I said, trying to act nonplussed while I’m pinching myself that I’m in Smokey Robinson’s hotel room. A few moments later his unmistakable falsetto voice carries from the shower; he’s singing his most popular song to date:

I did you wrong, My heart went out to play,

But in the game I lost you, What a price to pay

I’m cryin’

Ooo baby baby

Here I was, a 22-year-old copyboy who’d wangled a freelance assignment with one of the most popular pop singers of the day and he’s singing in the shower. I wanted to call somebody and tell them but I couldn’t. It was like making a hole in one by yourself, with no one around to verify it.

When he finally came out to talk, he was polite, sincere and genuinely engaged in our conversation. It’s interesting to look back at his comments about race relations more than four decades ago and see how things have – or haven’t – changed.

I went back to the Chronicle and wrote the following, published April 1, 1970.

“Hey Man, do you wanna be loved?” says Smokey Robinson to a ringside customer at Mr. D’s. “Every now and then,” the young man replies.

“Every now and then?” Smokey laughs in mock disbelief. “Oh, man, I wanna be loved ALL the time!”

Does he really want to be loved ALL the time? “Sure, man, everybody does. Don’t you?” No argument there.

“You know what I really dig?” he asks later in his room at the Miyako Hotel, as he slips a T-shirt over his short, Afro-style hair. “I dig people. I’m all for humanity.”

Robinson, at 30, has been digging people ever since he can remember – and music. Lead singer with the Miracles, now at Mr. D’s through Saturday, he is also vice president of the Motown Record Corporation – the main outlet for Rhythm and Blues music in America. He is a composer, arranger and an extremely gifted lyricist. A dynamo. Bob Dylan calls him today’s greatest living American poet.

People say I’m the life of the party ‘cause I tell a joke or two

Although I might be laughing loud and hearty, deep inside I’m blue

So take a good look at my face

You’ll see my smile looks out of place

If you look closer it’s easy to trace

The tracks of my tears

But despite all that, Robinson possesses no small degree of modesty. Beneath the glitter of his performing get-up – a gold satin Tom Jones-style shirt with purple ruffled front, a sleeveless purple jacket with gold lame trim, high-waisted bell-bottom pants and black patent leather shoes – is a warm and unaffected person.

“Man, for me life is a whole gob of experiences. Every day you go through so many experiences. They say it’s the best teacher. I can dig that, but I don’t have to experience everything myself to know what it’s like.

“I can just feel it. When I write a sad song it isn’t consciously because of some personal experience. I’ve never consciously written a song from personal experience.” He has written hundreds.

“There’s just so much sadness in the world today. It’s really an abundant thing when you think about it. And I can feel it.”

Although he and the Miracles (Pete Moore, Bobby Rogers and Ronnie White) have been making hits for 16 years, Smokey admits that his success long ago surpassed his wildest dreams.

“I used to go to class with a transistor radio plugged into my ear. We were recording when we were in high school and I’d listen for our record.”

When he dropped out of junior college in his home town of Detroit to pursue his desire to sing, his father, a city truck driver, was disappointed. “He told me if it didn’t work out, to go back to school.” He never went back.

The Miracles performance is virtually unchanged after 16 years, except that Smokey’s wife of ten years, Claudette, no longer travels with them. She still records with the group in Detroit, however.

“I made her stop, man. It was killing her. I’ll tell you how hard it was on her. She had six miscarriages.”

The Robinsons now have a son, 19 months old, with a name that reads like the Acknowledgements sections of a book – Berry (after Berry Gordy, Motown president and Smokey’s dearest friend), Borope (a combination of the first two initials of the first names of the Miracles) Robinson.

Smokey’s feeling for all people is the reason behind his decision to use the stage as an outlet for a personal crusade for the rights of black people.

“Look here, I don’t have to get up on stage and tell the people I’m black. Man, they can SEE that!” Smokey stops, stands up and walks over to the closet. “Don’t get me wrong now,” he says, buttoning up a knitted leather and wool latticework cardigan, “this is a beautiful history period for black people. They’re becoming aware of their blackness and they’re digging it!

“But there’s a time and place for everything, I think. I’m proud of my black heritage, sure, but I don’t think the stage is a place to lecture about it. The people come to be entertained. They want to hear “Ooo baby baby” or “Goin’ to A Go Go” or “Tracks of My Tears,” not a lecture. Young people get lectures every day.

“Like I said, I’m for humanity first. I don’t care if a guy’s black, blue, white or orange.” He smiles. “Anybody who’s not a bigot is cool with me.”

Smokey’s lyrical talents have won him two gold records and the top composer’s award from Broadcast Music Incorporated. “I haven’t changed my style much. I try to avoid the new fads, like the psychedelic trend, for instance. I want to write songs that will mean something to people 20 years from now.

“I’ve got no plans for slowing down yet. Motown still has growing pains and I’m going to keep writing songs for a long time.”

Write on, Smokey, write on.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR