DAN WHITE TRIAL

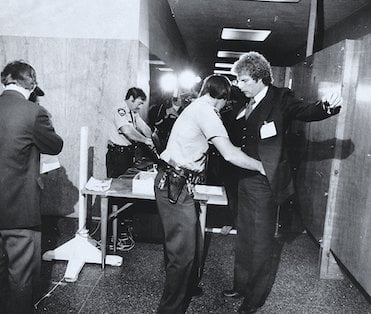

Duffy, entering the courtroom

One March morning in 1979 city editor Dave Perlman called me up to his desk. “Bill (German, the managing editor) and I want you to cover the Dan White trial,” he said. “We think you’ve earned it and you know all of the key people better than anyone else.”

I was both surprised and gratified. I was hoping to get the assignment but there were other longtime trial veterans on the staff and I knew this would be the city’s biggest story of the year up that point. I had been the paper’s city hall correspondent during the first two years of Mayor George Moscone’s administration and knew Moscone very well. I had also been a crime reporter before that and was very familiar with the board of supervisors, the city’s homicide detectives and the prosecution team. So it made sense that I would be considered.

At the same time, I was struggling with personal issues, having been separated from my wife for several months and missing work owing to depression and late night partying. Few of my colleagues and editors were aware of the depth of my depression, but for weeks I had doubted my abilities to concentrate and perform at a high level.

This, however, was exactly the shot of confidence I needed. I told Perlman of course I would do it and thanked him profusely.

On April 21, I wrote a long advance piece about the upcoming trial, a “scene-setter” as we called it, outlining the people who would be involved, the prosecution and defense strategies, the political environment behind the killings, and Dan White’s background. It began:

“Daniel James White, a single-minded political neophyte in a city of widely varying social and political values, goes on trial for his life next week, charged with the murders of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk in City Hall last November 27.

“For White, a fierce competitor who calls himself ‘a believer in the American dream that a person can do anything he wants when he puts his mind to it,’ this will be the toughest of all his personal battles.

“And for the city, the trial of the 32-year-old former supervisor for killing two popular elected officials will be a test of its own ideals – that government can function objectively even when torn asunder from within.”

The article noted that security at the trial would be inordinately tight, that reporters were coming from around the nation, and everyone entering the courtroom would pass through a metal detector and be patted down by sheriff’s deputies.

A thick shield of bulletproof glass would separate the audience from the forward arena occupied by the judge, attorneys, defendant and the jury. Prosecutor Thomas Norman said he expected to call some 20 witnesses, while White’s lawyer, Douglas Schmidt, planned to call twice that many. The trial was expected to last four to six weeks.

Judge Walter Calgano had reserved two wooden chairs inside the glass shield for reporters from the city’s two daily newspapers – me and my colleague from the San Francisco Examiner, the highly respected Jim Wood. The remaining press were to sit in the gallery behind the glass or in an overflow auditorium down the hall, where three 21-inch closed-circuit TV monitors were set up to view the proceedings.

On April 25, I reported to Department 21 of the Superior Court at the Hall of Justice at 850 Bryant Street for the first day of jury selection.

From my seat inside the glass I could see White’s face clearly, as well as those of defense attorney Schmidt and assistant DA Norman at the prosecutor’s table.

For the next four weeks, I observed the proceedings. During breaks I waited in the nearby press room with other reporters. Often they asked Jim Wood and me questions about things they might not have been able to hear or see from their vantage points.

At the end of each day’s testimony, generally around 4:30 p.m., I drove the six blocks back to the Chronicle offices and wrote my account. Using a manual Royal typewriter, it generally took me about 45 minutes to write five to six tripled-spaced pages, or some 1500 words, for the first edition. For later editions I added more material and cleaned up my earlier work.

Testimony began May 1 and the case went to the jury May 16. After five days of deliberations, we received word in the press room that the jury had reached a verdict. I returned to my seat in the courtroom for the conclusion of the trial. What we heard would stun the city and send it reeling into chaos and rioting well into the night.

Here’s my story that ran on the front page the following morning:

May 22, 1979

Dan White was convicted by a jury of two counts at voluntary manslaughter yesterday for the killings of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk in City Hall last November 27.

White, 32, who faced a possible death sentence if convicted of first-degree murder, could now receive a total maximum prison term of seven years and eight months for the manslaughter convictions and related charges.

With good behavior, he could be eligible for parole in about five years.

The former city supervisor, fireman and policeman dropped his head and rubbed his eyes as the verdicts were read in a packed, emotion-charged courtroom at the Hall of Justice at 5:28 p.m.

Several jurors — many of whom had cried listening to White’s anguished taped confession on the third day of the trial May 3 — wept openly while court clerk Anne Barrett read the verdicts.

White’s wife, Mary Ann, cried with joy and embraced White’s sister, Nancy Bickel, as Superior Court Judge Walter F. Calcagno polled each juror individually to confirm the verdicts.

It was the climax of six days of jury deliberation that began last Wednesday following an 11-day trial.

Defense lawyer Douglas R. Schmidt, who called five mental health experts to testify that White was mentally ill from severe depression, reacted to his major victory with subdued elation.

“There’s nothing I can say that will help the families of the victims, but the verdict is just,” Schmidt said in a Hall of Justice corridor jammed with reporters and television equipment minutes after the verdicts were announced.

“It was a tragedy.” Schmidt said of the shootings that stunned San Francisco nearly six months ago. “Now it’s behind us.’

He said White, who walked expressionlessly out of the courtroom to return to his jail cell after the verdicts, was “guilt-ridden and filled with remorse “

“He’s in very bad condition at the moment.” Schmidt said.

A stern-faced District Attorney Joseph Freitas said the jury’s conclusions were “somewhat of a tragedy.”

“I don’t think justice was carried out,” Freitas said. “I’m very, very disappointed. There were two charges of first-degree murder and the evidence was there to support that verdict.

“It’s a wrong decision. The jury was overwhelmed by emotion. I don’t think the jury analyzed the evidence properly. I think the jury was struck by his wife, his background and the politics of the case.

“I don’t like it and I think the people of San Francisco will be disappointed,” Freitas said.

Assistant District Attorney Thomas F. Norman, who had said earlier that he put on a flawless case for the prosecution, was downcast and grim.

“There’s little that I can add,” Norman said. “Tragically, there are so many people who feel great sympathy for Dan White.”

Mayor Dianne Feinstein, who was appointed to replace Moscone after the killings and whose testimony at the trial reduced the stone-faced White to tears, greeted the verdicts with “disbelief.”

“As far as I’m concerned, these were two murders,’’ she said.

Gina Moscone, the mayor’s widow. declined any comment on the results of the trial, according to a family spokesman. She did not follow the trial in the news media, he said.

Harvey Milk’s brother, Robert Milk of Long Island, said be thought the verdict “would be something more severe,” but that he had not wanted White to die in the gas chamber.

The jurors, who had been sequestered at the Jack Tar Hotel since the beginning of the trial, collectively decided not to discuss their deliberations publicly.

Although they were obviously exhausted by the experience and some cried with the reading of the verdicts, at least one juror wore a broad smile as he entered the courtroom.

Jury foreman George Mintzer, a Bechtel executive, handed the written verdicts to a bailiff, who gave than to Calcagno. The judge read them silently, then handed them to Barrett to be read aloud.

White, dressed in a tan sports coat and brown slacks, remained seated at the defense table with Schmidt and associate defense lawyer Stephen J. Scherr beside him. White did not look at the jurors, but stared straight ahead as he had throughout the trial.

Freitas, Norman and homicide inspector Frank Falzon sat at the prosecution table, closest to the jury.

As Barrett began to read the verdicts, Schmidt’s chest heaved and courtroom spectators perched stiffly on their seats, craning for glimpses of White and the jurors through the bulletproof glass partition.

The jury found White guilty of voluntary manslaughter and of using a firearm in both killings.

The only state of mind required for voluntary manslaughter is intent to kill. By its verdicts, the jury determined that White could not have premeditated, deliberated or harbored malice — the elements necessary for a murder conviction.

The penalty for voluntary manslaughter is two, three or four years in prison.

Under sentencing laws, White would receive four years on the first conviction for voluntary manslaughter, half the minimum — or one year — for the second conviction, and an additional two and two- thirds years for the gun-use finding.

After each verdict was read, Judge Calcagno asked each juror if that was indeed his or her verdict.

One by one, they replied: “Yes, your honor.”

The judge set a pre-sentencing report for June 19, then thanked the jurors profusely for their “very, very hard work” and said “the people of San Francisco owe you a debt of gratitude.”

Jurors Helga Soulie, Patricia Powis and Darlene Benton were still wiping tears from their cheeks as the panel left the courtroom.

Schmidt and Scherr stood to shake their hands and thank them, while the prosecution team remained seated — stunned and motionless.

The dramatic highlight of the trial came when the prosecution played a 24-minute tape recording in which White was heard confessing to the slayings of Moscone and Milk.

His voice anguished and halting, White was heard saying there was a “roaring” in his ears as Moscone calmly asked how White’s family was reacting to the controversy over his failure to gain reappointment.

White wept during the confession, as did his wife, one of his lawyers and a number of courtroom spectators. “I just shot him,” he said of the Moscone slaying. “That was it. It was over.”

Calmly reloading his gun, White then headed toward the supervisors’ offices, where Milk was encountered. “He just kind of smirked at me . . . and then I got all flushed and hot and shot him,” White said.

During the trial, the defense portrayed White as a fundamentally decent man who had, however, a rigid and unbending view of morality.

This inflexibility and inability to compromise led to a growing inner torment as White watched with disgust the horse-trading normal to politics, the defense contended.

Pressures built on White — financial, family and political — until they brought him to the breaking point, defense lawyer Schmidt contended.

The tip-offs were the spells of withdrawal and the recourse to junk food by the fitness-conscious former cop and fireman, he said.

The seeds of the tragedy were sown November 10 when White resigned his supervisorial seat, complaining that the $9600 salary was too low to make ends meet. The city attorney earlier had ruled that White had to resign his job as a fireman because of conflict of interest.

White and his wife had a new baby and she had quit her teaching job. A new restaurant at Pier 39 was making excessive demands on his time and energies, White said.

But no sooner had he resigned than his political supporters brought pressures to bear to have White withdraw the resignation. Finally, be buckled and five days later asked for the seat back.

“A man has a right to change his mind,” Moscone told reporters when he appeared determined to reappoint the supervisor.

But behind the scenes, a campaign was waged by board liberals led by Milk to deny White reappointment to a seat he had come to regard as his own.

“I no longer feel duty-bound,” the mayor concluded at last, “to reappoint Dan White.” Those words were to seal Moscone’s doom.

Moments before Moscone was to announce that he had appointed Don Horanzy to the District 8 seat held by White, White sneaked into City Hall, using a window to avoid the metal detectors at the door.

Moscone was killed by four bullets, including two fired into his head as a coup de grace. Moments later, Milk was cut down in another fusillade.

Schmidt succeeded in persuading the jury that the killings were not the work of a coldly rational killer, but the unpremeditated outburst of a man who bad been pushed over the edge and no longer, able to weigh the factors involved in the act.

“These were two cold-blooded, premeditated executions, and that’s all they were,” responded prosecutor Norman. In the end, though, the jury did not accept this explanation for White’s actions.

The key to the denial of the prosecution’s reconstruction of the events of that tragic day was the testimony of four psychiatrists called by the defense. Together, they established a reasonable doubt that White was sane on the day of the crimes.

Psychiatrist George F. Solomon testified, “It’s inconceivable for Mr. White, who couldn’t even tell off someone who stepped on his toe in a line, say, to plan something heinous.

“Good people — fine people with fine backgrounds — simply don’t kill people in cold blood.” was the way lawyer Schmidt put it.

“The mental illness, the stress and emotion of that moment, simply broke this man,” he told the jury. “He was honest and fair — perhaps too fair for politics in San Francisco.”

AUTHOR

AUTHOR