CITY HALL ASSASSINATIONS

Monday, Nov. 27, 1978. 10:35 a.m.

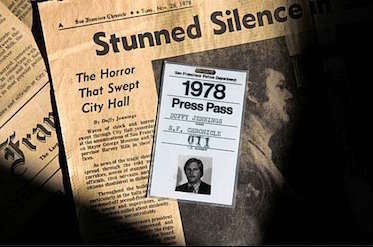

I’m sitting at my desk in the city room on the third floor of The Chronicle at Fifth and Mission streets, reading the newspaper and waiting for a story assignment.

A moment later, assignment editor Richard Hemp beckons me urgently as he hangs up a call from Bob Popp, our police beat reporter stationed at the Hall of Justice.

“On the way, Dick,” I answer, already out of my chair, grabbing my coat and notebook. “What do we know?”

“Report of a shooting is all. Call me from the car.”

In front of him on the desk stands a small microphone wired directly to head photographer Gordon Peters down the hall. Hemp leans in to the mike, presses down the button. The radio crackles to life.

“Shots fired at City Hall, Gordo. I’m sending Duffy.”

“Roger, Dick,” Peters responds. “Clem’s up.”

I meet photographer Clem Albers hustling out of the photo lab. We rush down to his blue Chevy Corvair staff photographer’s car parked behind the building and take off up Mission for the short ride to City Hall. Rounding the corner at Seventh, I lift the two-way radio microphone from its holder on the dashboard, pull it to my chin and push my thumb down on the talk switch.

“Jennings to desk. Any more details, Gunny?” I ask Hemp, an ex-Marine Corps gunnery sergeant who at 59 still walks with a drill instructor’s upright swagger and wears his dress shirts heavily starched and creased in the back. An ex-Marine myself, I use the Corps’ informal term for his rank.

“Popp says the mayor may have been shot,” Hemp replies. “And now we have shots fired in the supervisors’ offices, too. I’m sending two more teams.

“Sandy’s on the beat today,” he continues, referring to reporter Maitland “Sandy” Zane. “Meet him up there, and call me as soon as you know more.”

“Aye, aye, Gunny. Over and out.”

Clem guns the accelerator.

At the same time Hemp gets the call about the shooting, San Francisco Examiner reporter K. Connie Kang, at her desk in the second-floor press room at City Hall, hears the same news from her city desk. She drops the phone, bursts out of her cubicle and runs past Zane. “SHOOTING IN THE MAYOR’S OFFICE!” she yells and races out the door. Zane leaps to his feet and chases after her across the building to Room 200, the mayor’s office.

Clem pulls up to the Polk Street entrance, parks diagonally against the curb. Black-and-white units converge from every direction, sirens wailing, tires squealing. My first thought is that this looks like a scene from “Dirty Harry.” I wonder if this is really just a movie shoot and we heard the police radio wrong.

We bolt up the front steps to the gilded entry doors, flash our press credentials at officers guarding the entry and vault the inside stairs two at a time up to Room 200. A chaotic scene unfolds. Plainclothes detectives, officers in uniform and city officials scurry in and out of the mayor’s main office door and through two side doors to the inner offices.

Off to my right, the elevator door opens, and out rushes KGO-TV reporter Peter Cleaveland. He almost collides with two fast-moving cops, one with his service revolver drawn, another holding a shotgun aloft. “GET DOWN!” one of them barks. Instantly, I drop into a crouch against the wall, glancing around for a shooter. Cleaveland tries to enter the mayor’s outer office.

“Not this time!” snaps the officer barring the door.

Two plainclothes officers emerge from a side door of the mayor’s offices. “El alcalde esta muerto,” one of them says in a hushed tone. Cleaveland and I recognize the Spanish words for “the mayor is dead.”

“Is that true, is Moscone dead?” I ask another officer. “Who shot him? Is Mel Wax here?” I am hoping that Wax, Moscone’s press secretary, will confirm something, anything.

“Wait’ll the chief gets here,” comes the terse reply. We wait.

This is so unreal, so confusing, I think. Why won’t they tell us anything? I wonder if this is connected to the mass suicides of the Peoples Temple cult at Jonestown, Guyana, only nine days before. Minutes pass. Reporters converge on the scene, all asking questions that go answered.

Just then, a side door to the mayor’s office opens and two coroner’s aides wheel out a gurney with a shrouded corpse strapped to it, heading toward the elevator, where they must stand it upright to fit inside. Surprisingly, Cleaveland’s cameraman, Al Bullock, squeezes into the elevator with them, dutifully filming the transfer down to the medical examiner’s van parked outside.

I dash across the building to the supervisors’ suite of offices on the Van Ness Avenue side of City Hall, where about two dozen reporters and photographers are gathered outside the main door, also guarded by uniformed officers.

Zane and two other Chronicle reporters, George Draper and Ralph Craib, are there with Kang. So are Barbara Taylor and Jim Hamblin from KCBS, KYA radio reporter Larry Brownell and news director Greg Jarrett, KPIX-TV newsman Ed Arnow, Dick Leonard from KGO radio, Bob McCormick from KFRC, Cleaveland and a dozen others.

We collect in small knots, compare notes on what’s known for sure. Two men are dead, police have now confirmed, but no names are disclosed. Fretful minutes pass while detectives scuttle by grim-faced and silent. Wild rumors spread that a Peoples Temple hit squad has taken out Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, that gunmen might still be lurking in the building. We’re buzzing with nervous speculation, fear, disbelief.

I duck back into The Chronicle bureau office just across the hall from the supervisors’ offices. I call the city desk to check in.

“I think Moscone and Milk are dead,” I blurt, adrenaline rushing, heart pounding in my chest. “Not confirmed … no suspect yet … they might still be here … can’t get into the mayor’s or supes’ offices … cops everywhere … it’s total chaos up here. We’re still waiting for some official word.”

Just as I hang up, Zane pokes his head in the door and shouts:

“Announcement in the hall in five minutes!”

I elbow my way into the crush of news people and others stampeding up the ornate marble stairs beneath the City Hall rotunda. The enormity of it all is finally starting to sink in. A double assassination?

At that moment, Board of Supervisors president Dianne Feinstein emerges from her office, closely flanked by Police Chief Charles Gain on one side and by her aide, Peter Nardoza, on the other, almost as if they are holding her up. She is smartly dressed in a royal blue jacket and skirt and a white blouse with a blue-and-white paisley scarf knotted around her neck.

Feinstein stops at the top of the stairwell. She is ashen-faced, staring straight ahead. I can’t remember ever seeing a more horrified expression. Looking over the anxious group of reporters in front of her, Feinstein fixes her gaze on me, her eyes drilling into mine as if we’re having a private meeting.

(In later interviews, Feinstein recalled that moment. “I remember going out and making an announcement,” she said. “I’ll never forget Duffy Jennings, for some reason. I saw Duffy, and I don’t know why I kept staring into those blue eyes of his and I couldn’t speak for what seemed like a long time. I kept thinking to myself, ‘how can I say these words to that innocent, cherubic face?’ It just didn’t seem fair somehow. I will never forget his eyes, the eyes of that group, the press and others. It was like the world stopped.”)

She is clearly steeling herself for what she is about to say. We all fall quiet. In the hush, the only sound is that of shutters click-click-clicking. Lights atop TV cameras are ablaze, bleaching the entire scene. I try to scribble notes, but my hands are shaking.

“As president of the Board of Supervisors,” she begins, her voice weak and trembling, “… it’s my duty to make this announcement.” She pauses, inhales deeply, exhales. “Both Mayor Moscone … and Supervisor Harvey Milk … have been shot … and killed.”

“JESUS CHRIST!” Zane yells. “OH MY GOD!” shouts McCormick. A collective gasp goes up, an outburst of audible shock and horror I’ve never heard from veteran news people, inured as they are to executions, war, riots, plane crashes. All around us, city workers shudder in disbelief, some sobbing.

Feinstein continues. “The suspect … is Supervisor Dan White.”

Without another word, she and the chief turn and walk back inside her office.

I call Hemp with the confirmation. “All right,” he says. “Draper’s writing the lead. Sandy will do White. You do City Hall, the reaction, the mood, what it’s like there. Call back when you’re ready.”

The city was in shock. So was The Chronicle.

Carl Nolte, the assistant city editor that day and still on The Chronicle staff, put it this way when we talked about it years later: “We didn’t know what the hell was going on. We just had one of our own guys (reporter Ron Javers) shot down in a South American jungle, now this. No one really knew much about Dan White. We knew our politicos could be weird, but they didn’t just shoot each other. It knocked a hole in what we thought San Francisco was about. It shook the city to its roots. It was a crazy-ass day.”

White surrendered soon after the killings. Six months later, I covered his murder trial, sitting with the late Jim Wood of the Examiner inside the bulletproof glass separating the trial participants from the courtroom gallery.

On May 21, 1979, when the astonishing verdict of voluntary manslaughter came in, I rushed back to the office, pounded out the story, then went back out to join the other Chronicle staffers covering the ensuing “White Night” riot at the Civic Center.

I was more distraught than I admitted publicly, even to myself, over Moscone’s death and White’s lenient verdict. As The Chronicle’s City Hall reporter during Moscone’s first two years in office, I knew the mayor well from our frequent briefings in the same back parlor where White gunned him down.

From time to time, his Kennedyesque charisma and my close relationships with some of his top staff tested my journalistic objectivity, and that was one reason I returned to general assignment reporting.

I didn’t realize it immediately, but a decade of one terrible event after another was taking its toll. I was barely out of my 20s, and I had already covered what many young reporters would consider a career’s worth of big stories.

The Zodiac case, the Patricia Hearst kidnapping, the Zebra killings, the Golden Dragon restaurant massacre – I had shared in the newspaper’s reporting on these sensational crimes and other major stories.

In between, I worked graveyard shifts on the police beat, went on call 24/7 with homicide detectives, was embedded in San Francisco’s busiest firehouse fighting fires with Engine Co. 21 and wrote about more death, disaster and destruction than I care to remember.

By 1980, I was burned out. I left the paper to be the San Francisco Giants’ publicity director and later went into a public relations career.

Two things about the City Hall killings stay with me today some four decades later. First, my eye-to-eye exchange with now-Sen. Feinstein burnished the moment into memory for both of us. Second is an understanding of how Moscone changed the city forever. Sadly, his legacy has been overshadowed by the memory not of how he lived, but of the way he died.

Moscone had his critics, some with good reason, but he loved San Francisco, a passion I share as a fellow native. An entire generation of San Franciscans today knows little about him other than the city’s convention center bears his name.

He fought against racism and for civil rights, against downtown power brokers and for neighborhoods. He opened the doors of City Hall and the seats of power to people from all walks of life, regardless of race, gender or sexual orientation. As deservedly iconic and significant as Harvey Milk has become to the gay community, it was Moscone who broke down the barriers.

Sean Penn won a best actor Oscar for his portrayal of Milk in the 2008 film, “Milk.” But the mayor’s story was remarkable in its own right. Perhaps one day, Hollywood will give us a movie titled “Moscone.”

© 2019 by Duffy Jennings. All Rights Reserved.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR